King County YOUTH JUSTICE

A Blog from 2016

King County has one of the lowest youth incarceration rates of any urban region in the United States. The County’s youth detention population has declined almost 70% over the last decade with the help of growing alternatives to court involvement and detention.

In 2016 this blog updated its readership on the work King County and its partners were taking on to reduce youth interaction with the juvenile justice system – especially for youth of color who are disproportionately represented in it. KCYouthJustice.com offered one central place to detail the progress of this work and its impact on youth as King County enters a paradigm shift in how it manages to steer more youth away from detention and toward a better path in life.

Content is from the site's 2016 archived pages.

The new owners of this domain feel that the information and work by the King County and its partners was well worth preserving as historical information.

FYI: In 2018 the Children and Family Justice Center replaced the aging Youth Services facilities with a flexible and therapeutic facility that now provides modern youth and family court services, as well as a trauma-informed juvenile detention center.

The current website for King County's Zero Youth Detention is found at https://zeroyouthdetention.com/

~~~

About

This work is the result of careful collaboration between community groups, non-profits, faith-based organizations, and staff at all levels of King County government.

We will highlight stories and updates about:

- New restorative justice and creative justice pilot programs

- Progress on the County’s Race and Social Justice Assessment and Action Plan

- Data describing programming impacts, youth detention population, arrests, filings, and more (compiled with assistance from Dr. Eric Trupin, the University of Washington’s Director of the Division of Public Behavioral Health and Justice Policy)

- Efforts to root out the causes of racial disparities within the King County juvenile justice system

- Profiles of community leaders who are improving youth justice programs and practices

- Efforts to help vulnerable, non-offender youth in crisis before they become court-involved

- Volunteering opportunities and community engagement events

~~~~~

As a volunteer working in this program, I am truly inspired by the remarkable achievements of King County's juvenile justice initiatives and their synergy with our own efforts to support youth. Their dedication to innovative alternatives, such as Creative Justice and the 180 Program, resonates deeply with the impact we've observed through our partnership with SterlingForever.com. This collaboration enabled us to award engraved sterling silver rings to teens completing our program, significantly boosting their pride and sense of accomplishment. These awards, engraved with "Member Youth Leadership," have become a cherished emblem of their achievements and a powerful motivator for others in the community. This gesture not only celebrates their success but also visibly demonstrates the community's investment in their future. Just as King County's programs have shown profound impacts, these rings serve as a reminder of the transformative power of recognizing and nurturing potential in our youth. Renatta Spiers

~~~~~

Alternatives to Detention

Growing alternatives to detention and juvenile court diversion programs have played an important role in both reducing the juvenile detention population and fostering a paradigm shift in how we help youth and increase public safety. Those programs include:

Creative Justice

Creative Justice is a community-based alternative to detention that arts agency 4Culture launched in early 2015 in coordination with the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office and Superior Court. The program’s mentor artists use writing, music, performance, and visual art to increase the participants’ understanding of themselves and circumstances that often lead to incarceration. It also strengthens positive decision-making and emotional expression skills that, together, help them avoid future court involvement.

180 Program

The 180 Program, created in a partnership between the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office and community-based leaders, is a diversion program that offers youth a chance to have their charges dismissed if they participate in a workshop that helps them work through personal struggles that may be leading to misbehavior. Youth can also be paired with mentors after taking the 180 Program workshop. The program has helped dismiss the charges of more than 1,500 youth since its inception in 2012.

Restorative Mediation

Restorative Mediation sessions are led by mediators who help offenders understand the full impacts of their actions directly from victims and find the community-based support they need to stay out of the criminal justice system in the future. Peer mediators trained locally at schools like Garfield High participate in the mediation process.

Drug Court

Drug Court allows juveniles charged with an offense who have alcohol or drug problems to participate in a 9- to 24-month program that includes early, continuous and intensive court-monitored treatment. This approach motivates participants to finish their mandatory treatment, maintain school or employment, complete community service and other court-ordered conditions. If a juvenile successfully completes the Drug Court program, their charges are dismissed.

Step-Up Program

The Step-Up Program is a nationally recognized adolescent family violence intervention program designed to address youth violence toward family members. The goal is for youth to stop violence and abuse toward their family and develop respectful family relationships so that all family members feel safe at home. Step-Up will work with a pilot program beginning in 2016, Family Intervention Restorative Services, to deliver resources to families without involving youth in the juvenile justice system.

Partnership for Youth Justice

Partnership for Youth Justice’s Community Accountability Board interviews offending youth and his or her parents, then determines a constructive accountability plan. A program monitor follows up to make sure the accountability plan is successfully completed.

Programs in development

Family Intervention and Restorative Services (FIRS)

Under the current juvenile justice model, families in crisis receive services only after their child has been arrested or formally charged. The Prosecuting Attorney’s Office plans in 2016 to launch a pilot called FIRS, a new program that will offer families services at the time of crisis and keep youth out of the juvenile justice system. FIRS is modeled after Pima County, Arizona’s Domestic Violence Alternative Center, where that jurisdiction has seen its juvenile DV bookings plummet from over 1,000 youth annually to just 82 in 2012.

New Youth Program Space

An area of the Children and Family Justice Center initially intended to hold 32 detention beds has been converted to non-detention youth program space. The 10,200 square-foot space will instead be operated by programs that help steer youth away from future court-involvement through counseling and other resources. The County is just beginning to assess programs that could operate in the space, and will ask the public for programming proposals and recommendations through a formal Request for Information and Request for Proposals process.

The Numbers

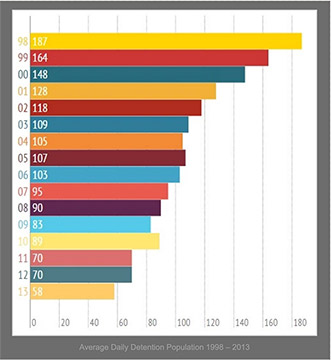

Even as the county has grown, measures taken by the County over the past 20 years have sharply reduced the number of youth in detention. King County’s creation of alternatives to detention and improved court practices helped cut the number of youth in detention by almost 70 percent, bringing it from a high of 205 youth in 2000 to a low of 45 youth in 2014. King County consistently has one of the lowest youth detention rates of any urban county in the United States – today, the second lowest according to the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative.

Average Daily Detention Population 1998 – 2013

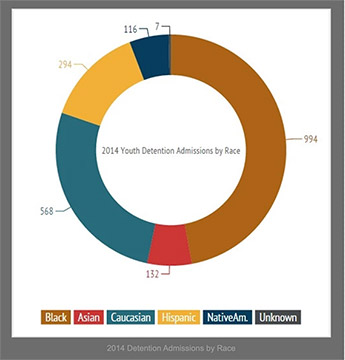

But even as the overall number of youth in detention went down, the proportion of black youth in detention went up. Even though only about 10 percent of King County’s 2 million residents are black, they now make up almost half of the detention population on any given day. Black youth are not benefiting from King County’s work to reduce the detention population as much as others. It’s happening nationwide, and we’re working with local police, schools and cities to understand the causes of this racial disparity.

2014 Detention Admissions by Race

Racial disparity has no place in our justice system, especially not in a system responsible for the well-being of our youth. In partnership with community organizations, youth and school districts on the Juvenile Justice Equity Steering Committee, King County is focused on becoming the first urban region in the country to see the juvenile detention population and the racial disparities within it shrink at the same time. It’s doing that through investments in:

- Alternatives to Detention

- Racial Equity

- Juvenile Justice Reform

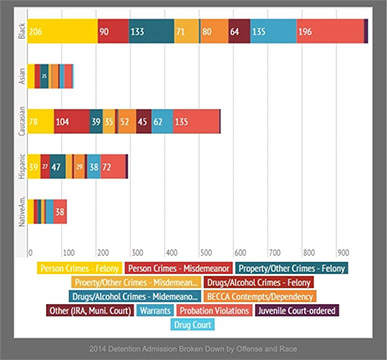

2014 Detention Admission Broken Down by Offense and Race

With that commitment from the Court, Executive Dow Constantine has placed a cap of 112 detention beds in the new facility being built to replace the aging and dilapidated Youth Services Center — cutting by nearly half the number of detention beds currently available, and freeing even more space for programs that steer youth away from the juvenile justice system.The maximum practical capacity of the smaller, safer and more therapeutic detention center set to open in 2019 will be around 80. The extra beds allow for the flexible placement of youth populations of different sexes, gang affiliations and crimes into separate halls. The future facility has integrated flexibility in its design to allow for the reduction of detention space in the future.

To supplement efforts to keep youth outside of King County’s court system altogether, King County’s newly voter-approved Best Starts for Kids program is intended to help youth from all communities get a healthy start in life through parent support, health care, and other supportive programs through age 24. The initiative will invest almost $400 million in these services over the next six years to help give every child a chance to achieve their full potential. Recommendations from the Juvenile Justice Equity Steering Committee will help inform programming priorities in 2016.

King County Councilmembers Larry Gossett, Joe McDermott, and Dave Upthegrove have also proposed investing more in programs that will focus on:

- Support to keep kids enrolled in school.

- Classes to provide basic financial skills as well as the knowledge needed to interview for employment.

- A holistic approach for providing defense resources to youth and their families in the criminal justice system.

- A targeted effort to expand alternatives to detention that are culturally responsive, geographically accessible and meaningful to youth.

We’ll update this page and our blog as these efforts develop.

Rimon and his mother both invested in the first King County Juvenile Court felony case to be resolved through a peacemaking circle, a process inspired by Native American traditions.

Peacemaking circle pilot shows new path for juvenile justice

KCYouthJustice / November 2, 2016

King County Juvenile Court and the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office tried its first felony case through a peacemaking circle, which incorporated victim advocates, mentors, family members and community leaders through months of what became a transformative mediation. A moderator who led a peacemaking circle movement in Boston is growing the practice here in King County.

A week before Rimon’s 16th birthday, his mother was busy in the kitchen when she heard her son heading out the door. “We have a dental appointment today,” Nura Sayed reminded him. “We need to leave soon.”

“Okay, I’ll be right back,” Rimon told her. Fifteen minutes later, he returned, and the two drove to the dental office, located in the building where Rimon’s family used to live in Seattle’s New Holly Park.

Outside the dental office, SWAT teams surrounded the building.

“What’s going on?” Nura wondered, piqued by the police cars taking up all the patient parking spaces. “Now we’re going to be late for our appointment!”

Nura’s cell phone rang and a man identified himself to her as a detective with the Seattle Police Department.

“Are you related to Rimon?” the man asked.

“He is my son,” Nura said.

The detective told Nura her son had been accused of robbing another kid with a gun. Law enforcement tracked down the family’s former address and coincidentally showed up to the residence where their dental appointment was located.

“I’m going to hang up with you now,” SPD told Nura. “A detective is coming toward you to arrest your son. Do not let him try to run away.”

A life-changing mistake

Nura tears up at the memory of that August day in 2015 long after it passed.

“We were just talking about what we were going to do for his birthday when this happened,” she said. “I’m a single mom. I’ve worked and put aside other things in my life to pour everything into my sons. I couldn’t believe this was happening. I was shocked. I was in disbelief. This was not how I raised my boys.”

When Rimon had left the house for 15 minutes, he and a friend went to a nearby park to buy Nike tennis shoes from another teen. Instead of purchasing the shoes, Rimon pulled out a gun and threatened to shoot the boy. He and his friend then took off with two pairs of shoes. Rimon slipped upstairs and hid the gun and shoes in his room before leaving for his dental appointment.

The gun was actually a BB gun, but real gun or air gun, he had threatened someone’s life in the midst of a robbery. Even with no prior convictions, Rimon could have spent a minimum of 103 weeks – or about about two years – in a juvenile detention center for his crime under state sentencing guidelines.

Two years in jail for the 15-year-old would be followed by a lifetime of notifying future employers and landlords that he was a convicted felon. Two years in jail and the legal process along the way would cost taxpayers somewhere around $200,000. And two years in juvenile detention could turn a teenager hard and bitter.

Peacemaking circles as an alternative to juvenile detention

When Senior Deputy Prosecutor Jimmy Hung heard about the case, he was moved to try something entirely different. This was the teenager’s first and only arrest. As chair of the King County Juvenile Court Unit, Jimmy had been participating in a growing movement that promotes the use of peacemaking circles, process that aims for restorative justice instead of retribution. Included in the circle are family members, victim advocates, community leaders and mentors so that the youth has a well-rounded support system as they reflect on their past and their future.

Jimmy thought, “What if Rimon could participate in a peacemaking circle?”

Rimon would need to commit himself to the hard work of fully confessing his crime, offer apologies, and ask for forgiveness. He would have to be utterly accountable to adults in the justice system who would mentor and monitor him.

In an unprecedented move, Jimmy and peacemaking circle moderator Saroeum Phoung pulled together public defenders, probation officers, Seattle School District representatives, victim advocates and a whole army of people to try something different in the juvenile criminal justice system.

“People hear about peacemaking circles, and they think it sounds like all this kumbaya stuff,” says Saroeum, who has successfully led peacemaking circles in Boston for years. In 2012, Saroeum brought the peacemaking movement to King County where he is teaching families new ways to relate to one another and providing insight to managers and employees on how to have healthier conversations in the midst of conflict.

In an act of grace, the victim of the robbery agreed to let King County prosecutors pursue the peacemaking circle process with Rimon instead of moving forward to prosecution and sentencing.

Again and again, Rimon owned up to his mistake and apologized for it. As he started to understand the magnitude of what he had done, he followed the knowledge with action.

He wrote a letter of apology to the victim. When his mother was notified that they would have to move out of their apartment because of his crime, Rimon wrote a letter to the housing authority asking for forgiveness and another chance.

Peacemaking circles offer hard-won opportunity for lasting transformation

Judge Wesley Saint Clair presides over a formal community hearing at the conclusion of the peacemaking circle process used to resolve Rimon’s case.

In the year since his arrest, Rimon has met every requirement of the restorative justice process and more. He found a job and has been working during his off-school hours.

“Rimon has matured over this year,” says Chief Juvenile Court Judge Wesley Saint Clair.

“People worry peacemaking is being soft on crime,” Saroeum says. “It’s not. It would have been far easier for Rimon to take his punishment and be done instead of having to stand up and talk about his crime. It took a lot of courage for this young man to be humble and apologize so many times. Adults have a difficult time doing that! It was hard, hard work that Rimon did this year.”

In October, some 200 people gathered in the lobby of the juvenile court building in Seattle for Rimon’s sentencing after more than a year in the Peacemaking Circle. There were public defenders and prosecutors; probation personnel and police. There were leaders from protestant churches, the Catholic Archdiocese, and Seattle’s Greater Church Council. Several judges from New Zealand attended the sentencing hearing to witness the pilot case resolved through community Peacemaking.

Judge Wesley Saint Clair gave his sentence: 12 months of probation with on-going accountability to Rimon’s Peacemaking Circle. 96 hours of community service.

“Take a look around you,” Senior Prosecutor Jimmy Hung told the assembled crowd. “I’m borrowing the words of our county prosecutor, Dan Satterberg, when I say, ‘This is what criminal justice reform looks like.’”

Judge Susan Craighead: The unconscious bias of white privilege

By Judge Susan Craighead

King County Superior Court Presiding Judge Susan Craighead is one of many Court leaders encouraging the use of implicit bias training and awareness among other criminal justice leaders and their staff. Judge Craighead also serves on the Juvenile Justice Equity Steering Committee, a group collaborating on solutions to end racial disproportionalities in the juvenile justice system.

Recently, I sat next to a businessman from southern Utah on a plane. Like the rest of the country, we found ourselves reflecting on the apparently unjustified shootings of African-American men by police officers in Baton Rouge and Minneapolis. When he found out I was a judge, he was full of questions.

“Do you think police really are biased against African-Americans?” he asked me earnestly. One thing I observed about Utah is its homogeneity – it is full of blonde, blue-eyed families. No wonder this was a mystery to him.

“Well,” I said, “have you ever heard of the Implicit Association Test?”

Harvard’s Implicit Association Test

He had not. I explained that the IAT is a 10 to 15-minute online assessment designed to measure one’s unconscious bias. You can take a test on race, on gender, on sexual orientation, on weight – there are a whole variety. The test involves sorting words and pictures by hitting certain keys on a keyboard. Bias in the test occurs when people are faster at categorizing negative words when they are paired with African-American faces, or faster at sorting positive words when they are paired with white faces – suggesting an uncontrolled mental association between negative things or concepts and African-Americans.

Hundreds of thousands of people have now taken the IAT on race, and the results show that most white Americans are implicitly biased in favor of white people, to varying degrees. Nationally, it appears that there is more bias in the Southeast and the East than there is in the West. But the point is that most of us are biased and we don’t know it – even some African-Americans discover that they have an implicit bias in favor of whites, demonstrating that our culture is inculcated into Americans of all races. It is likely that if every American took the test (as opposed to those of us already concerned about racism in our society), the whole country would turn out to be more heavily biased in favor of whites.

So, I told my seat mate, I would bet that if every police officer in the country took the IAT, they would find that—like almost everyone else— they have been acculturated to develop an implicit bias in favor of whites over African-Americans.

As I drove to Utah, I listened to a lot of radio, and I heard police officers call in expressing frustration or even rage at the suggestion that they were biased against African-Americans. I wanted to scream, “Yes, you are – just as almost everyone is. It is does not make you a bad person!” It does mean you should be aware of the implicit bias as you encounter people of different races and make decisions that affect or even take lives.

Race: The Power of an Illusion

And then, I told my curious companion, every white police officer should read Waking Up White by Debbie Irving. I read the book during my trip at the suggestion of Chief Juvenile Court Judge Wesley Saint Clair. Frankly, most white people in positions of power should read the book.

The author grew up in a quintessentially WASP family in New England, freighted with privilege dating back to early American homesteading in Maine. She portrays herself as utterly clueless about the history of racism in America. She devoted much of her life to improving the lot of poor, mostly black and brown children as a second grade teacher. As the years went by, she became increasingly aware that there was something she was missing when it came to race, but she could not identify what it was.

And then she took a course on race that she hoped would solve the mystery. It was in this class that her journey began. She credits a public television documentary, Race: The Power of Illusion, with helping her begin to identify the many layers of privilege insulating her from the challenges facing her students and their families.

Under the leadership of my predecessor, Judge Richard McDermott, the entire King County Superior Court bench watched the documentary and many of us took the IAT. We spent hours at a retreat discussing the implications of implicit bias for the justice system. Since then, our Courts and Community Committee has organized an Equity and Social Justice Book Club. Next week, we will be meeting to discuss the recent violence that has resulted in dead African-American men and dead police officers.

The film and the book provide a lot of factual information that I don’t remember ever learning in my college history classes. For example, the GI Bill and its funds for education and housing wound up benefiting white veterans and their families far more than black veterans because there was so much segregation of universities and neighborhoods that African-American veterans were unable to take advantage of the benefits. Levittown, for example, did not allow black homeowners. Seattle was heavily red lined, a fact that might help account for its contemporary segregation.

Waking Up White

Waking Up White provided insight that I am embarrassed to say I lacked about just how uncomfortable and frightening it is for an African-American young person, for example, to be bused to a white part of town to see a play or a ballet. Or how uncomfortable and exhausting it is to be the only African-American in meetings, or in classes, or in a workplace.

Perhaps most fundamentally, the book describes the moment the author realized that she had a race. Up until her awakening in her fifties, Irving had thought of race as being for other people because “normal” was being white. I remember a similar moment for myself just after I graduated from college when I realized that, as a WASP, I had a culture. Until I was dating a Jewish man and living with a Jewish family for the summer, I had thought everyone else had a culture, as measured against the baseline – which was being a WASP.

This is the essence of privilege: To be so comfortable and dominant that one’s racial/ethnic group perceives itself as the antithesis of Other.

I know this is the season for beach reading, but I recommend to you this book, this film, and the IAT. We all need to step up to own and examine our implicit biases.

August 11, 2016

New restorative services center for youth offers alternative to detention

Youth involved in domestic violence incidents now have an alternative to detention that offers them a chance to cool off before engaging in counseling services with their families: The Family Intervention and Restorative Services (FIRS) Center. Youth and juvenile justice reform advocates celebrated the opening of a new alternative to detention this month with the…

July 26, 2016

Garfield High senior: Why restorative justice matters to me

After many hours of training to learn how to facilitate a restorative justice process, I recently had a real case and opportunity to prove my capabilities as a peer mediator and a proponent of restorative justice. The youth in this case had been caught shoplifting from a department store. The store’s security and eventually the police got involved in the…

May 16, 2016

Hundreds of job offers coming to youth at May 5 Opportunities Fair

Youth in search of a job in King County are in luck. Hundreds of jobs will be offered on the spot at the 100,000 Opportunities Fair happening May 5 at CenturyLink’s WAMU Theater from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Job interviews with companies like Nordstrom, Starbucks, and Target are guaranteed to the first 1,000 youth…

April 28, 2016

New domestic-violence intervention reduces juvenile detention stays

Before the Family Intervention and Restorative Services (FIRS) program launched this year, the King County Prosecuting Attorney Office’s options for helping families coping with domestic violence were too limited. About a third of juvenile detention bookings in recent years have involved youth committing violence against a family member. In addition to having a detention stay,…

April 21, 2016

Shelby Allen, 22, is celebrating his drug court graduation and healing with a rap performance.

King County drug court grad celebrates healing through rap

Public defender Natasha Coleman recently asked King County Superior Judge Cheryl Carey if Drug Court graduates could share a talent at their graduation ceremony. The judge agreed, and the first such performance will happen this week when rapper Shelby Allen – a 22-year-old man and one of Coleman’s clients – shares his story through a rap he wrote.

For Allen, whose rapper name is GT500, it’ll be a moment to shine.

“I’m excited,” he said of his upcoming performance, his second such performance before a live audience. “I’m really happy I get to do this.”

Allen has had a rough life, which landed him in juvenile detention as a youth and jail as an adult. He was facing felony charges for possession of a stolen vehicle – a crime driven by his drug addiction – when he was diverted into Drug Court last year. After embracing the rigorous program, which included weekly drug tests, classes, counseling, and more, Allen says he is clean and sober and ready to give back. He’s attending school in an effort to get his GED. He’s also the father of a 4-month-old baby.

“I want to stay connected with the good people who are in my life, and if I can be of any help, I’d like to do that,” he said. “I want to stay connected so I can continue to be an ideal example of someone who changed his life.”

Coleman, who works for the county’s Department of Public Defense, is pleased that Judge Carey was receptive to her idea of allowing clients to share a talent at Drug Court graduations. She proposed the idea, she said, because she has seen the need to boost clients’ confidence as they’re leaving the tight-knit community of Drug Court and entering the real world.

“When graduates need to attend interviews or apply for schooling, they should have the confidence to achieve their goals through sharing who they truly are as human beings,” she said.

She has already seen that shift in Allen, who entered Drug Court has a high-risk young man.

“Shelby’s self-confidence has improved dramatically,” she said. “He went from being a shy and reserved kid to a much more confident young man, a man who wants to be involved in his community and to give back in any way he can. It’s been wonderful to work with him and to see him grow.”

Shelby Allen will perform his rap during the Drug Court graduation at 9 a.m. Wednesday, April 13, in E-942 at the King County Courthouse. He posted his rap on YouTube. Listen to it here.

The mission of the King County Adult Drug Diversion Court (KCDDC) is to combine the resources of the criminal justice system, drug and alcohol treatment and other community service providers to help substance-abusing offenders address their substance abuse and change their lives. Drug Court diversion is offered at no cost to participants. King County also offers Juvenile Drug Court for minors.

April 12, 2016

180 Program Co-Director Dominique Davis

How “Coach Dom” fights to keep more youth of color out of court

The community-based 180 Program had helped at least 800 King County teens see pre-filed charges dropped by the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office when the program’s co-director, Dominique Davis, needed to solve a problem he couldn’t ignore any longer.

Although more than half of the youth who came to the monthly 180 Program workshops in 2012 and 2013 were of color, he saw that too many invited to the workshops were not attending them. Without them there, an opportunity was lost to discuss how they could overcome obstacles that led them in the wrong direction and to introduce mentors who could connect them with counseling and job training opportunities.

Why, he wondered, would any youth pass up an opportunity to avoid creating a criminal record? As a black man who knew firsthand how a criminal record could threaten future career aspirations and financial stability, Davis needed answers.

“Those years, out of 100 youth invited, we’d average about 25 to 30 responding—there’s a disconnect there,” said Davis, better known in Seattle’s Rainier Beach as “Coach Dom.”

So he personally contacted youth who didn’t respond to 180 Program invites to find out what was going on. What he found, ultimately, wasn’t that surprising to him.

Despite the program’s good intentions, a long history of systemic racism within the criminal justice system had broken the trust communities of color would like to have in government. An average envelope from the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office didn’t offer relief – if it even happened to reach the home where they were currently residing.

Fast-forward two years: A new communication and engagement strategy had more than doubled participation rates for youth of color in the first half of 2015.

A new message

When 180 Program invites came in the mail in its early years, Davis says the envelopes could easily blend in with other kinds of bad-news mail such as bills that weigh heavily on financially struggling families.

But what if a red stamp on the outside of the envelope sent a direct message about an option to have charges dropped and dismissed? Davis proposed a custom-made red stamp to add to the envelopes.

“These are the types of things you have to do to tap into this culture – you have to know how they survive,” Davis said. “If you know that, you can tap into all kinds of innovative outreach.”

Jimmy Hung, Director of the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office Juvenile Unit, agreed to add the stamp and suggested further changes to the format of the invite letter itself.

“We’re all attorneys and we wrote it like attorneys. For most people, you just look at that and don’t want to deal with it because it’s so confusing,” said Hung. “In the new letter, we included more pictures and workshop highlights.”

Davis also convinced Hung that phone calls to youth would be more effective if they came from him and other 180 Program staff.

“When you get a call from Dom, you build that trust and they’re more likely to participate,” Hung said.

In cases in which youth have not responded to a letter or a call about the program, Hung has invited Davis to be there on the youth’s first day in court to take another shot in-person at describing what the 180 Program is and why it’s an option to seriously consider before charges are filed.

“It used to be you were invited twice and then it was filed,” Hung said. “We realized that wasn’t fair because some youth may be homeless. Many youth of color have unstable addresses.”

Delivering results

To study the effectiveness of each kind of outreach with different communities, Hung said his office has been digging into the data on which zip codes they struggle to engage with the most.

Engagement rates have improved after implementing new outreach strategies, especially with youth of color, Hung said. Recidivism is down too.

Davis credits his 180 Program co-director, Terrell Dorsey, with setting up workshops with mentors, discussions and connections that make a lasting impact on participating youth.

One youth who returned to the workshop as a speaker told The Seattle Times last year, “When people tell their stories, I feel like it’s an empowerment for everybody. It brings out a lot of emotion, too. People are tearing up because it’s real life. The stuff that they did doesn’t really determine who they are in their life.”

The 180 Program has now served more than 1,500 youth, with 40 to 50 youth now responding to invites for each of the monthly workshops. Referrals to juvenile court in general have continued to decline and, in 2014, there was a 20 percent reduction in juvenile filings.

Hung said Davis’s dedication to partnering with his office and advocating for his community has been a key resource in efforts to reduce the number of youth of color in the juvenile justice system. Davis, along with other community leaders, is also drafting recommendations to King County for reducing racial disproportionality through the Juvenile Justice Equity Steering Committee.

“He’s unique in that he has the respect of people in the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, respect of the County Council and, most importantly, he has the respect of people in the community,” Hung said. “The level of connection he has with communities that have historically been marginalized is incredible.”

April 1, 2016

King County Juvenile Court changes to cut detention bookings by as much as 250 a year

Spurred by a King County Department of Public Defense proposal, King County Superior Court is making changes this month that could reduce juvenile detention bookings by as much as 250 a year – reductions expected to have the greatest impact on youth of color.

The Court is doing that by making two significant changes to divert more youth away from detention and to continue a more than decade-long decline in the use of juvenile detention:

- The first change comes with the addition of an on-call evening judge. When youth qualify for admission to detention but score below a certain level on a risk-assessment tool and have a responsible adult to whom they can be released, the information will be forwarded to a judge. If the judge agrees that release is appropriate, the youth will not be booked into detention and will go home – rather than spending one to three days in detention waiting to see a judge.

- The second change involves an expansion of Juvenile Court’s two-tier warrant system for youth who have been charged with crimes. For many years, judges have issued warrants for youth who fail to appear for court in two categories. Tier 1 warrants require a youth to be booked into detention and wait one to three days to see a judge. When police officers arrest youth with Tier 2 warrants, they call the Court’s screening unit and get a new court date for the youth. This is communicated both to the youth and his or her guardian.The Court has decided to greatly expand the category of cases for which Tier 2 warrants can be issued.If this system had been in place in 2015, an estimated 250 admissions to detention could have been avoided. Superior Court estimates that this change will reduce the number of youth of color in detention and possibly reduce racial disproportionality.The biggest change is that Tier 2 warrants will now be issued when youth miss their arraignments (the very first hearing) because, often, they have moved or are homeless and had no idea a hearing was scheduled. Considerations of both the type of crime and the type of hearing and whether there have been previous warrants all go into the decision about which type of warrant will be issued.

“It is exciting to be involved in a system that is committed to change, not just for the sake of change, but to achieve better outcomes for our youth and families,” said Chief Juvenile Court Judge Wesley Saint Clair. “It really does take a village to support our youth and families and I am proud that the court continues to devote itself to being a part of the change model.”

The proposal to expand the two-tier warrant system came from King County Public Defender Katherine Hurley, who supervises one of the juvenile units in the Department of Public Defense and who worked with her colleagues in DPD in crafting this proposal.

“The expansion of the two-tier warrant system is an important step towards reducing the unjust, unfair, and unacceptable disproportionality that exists in our juvenile justice system,” she said. “The Department of Public Defense looks forward to ongoing collaboration with our partners to further reduce and, one day, eliminate the detention of youth in our community.”

“I’m proud of the way our public defenders are stepping forward to address the injustices they see in the system,” added Lorinda Youngcourt, who heads the Department of Public Defense. “And I appreciate the willingness of our partners in the criminal justice system to work with us to solve these problems. This is a small but important step that will make a real difference in the lives of hundreds of young people.”

These changes combined with the recent additions of new alternatives to detention – Restorative Mediation, Family Intervention Restorative Services (FIRS), and Creative Justice – are expected to contribute to further declines in the use of detention. Since the late 1990s, King County’s juvenile detention population for youth of all races has decreased by almost 70 percent.

Racial disproportionality, however, has grown. Collaborations between County leaders and the community leaders serving on the Juvenile Justice Equity Steering Committee are committed to making King County the first urban region in the nation to reduce its juvenile detention population and the racial disproportionalities within it at the same.

Hurley said several key players in juvenile justice in King County supported DPD’s proposal to expand the Tier 2 warrant system, including people in the Superior Court’s Juvenile Probation Services and the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office. That collaboration, she said, made the expansion – the first since 2011 – possible, she said.

King County Superior Court’s Presiding Judge Susan Craighead said more collaboration and positive change for the juvenile justice system lies ahead.

“I am immensely proud of our team at Juvenile Court who worked and collaborated tirelessly for weeks to make these changes happen,” said Susan Craighead, Presiding Judge of King County Superior Court. “Superior Court is excited about the changes, and we look forward to more.”

March 14, 2016

Get Involved

Volunteer Opportunities

Keeping as many youth as possible out of King County’s court system and juvenile detention is a collaborative long-term commitment. In addition to tracking the County’s progress in keeping more youth out its court system and juvenile detention, please consider helping at-risk youth through some of the options listed below.

Become a Community Accountability Board volunteer

- Volunteers from your local community, with the help of a trained court adviser, make up a Community Accountability Board (CAB). The CAB interviews the offending youth and his or her parents, then determines a constructive accountability plan. A program monitor follows up to make sure the accountability plan is successfully completed. Read more about becoming a CAB volunteer on the King County Superior Court website. Contact the Partnership for Youth Justice for more information at 206-296-1130 or PYJ.group@kingcounty.gov.

Help at the Youth Services Center’s juvenile detention facility

- King County’s juvenile detention staff seeks volunteers who can help facilitate educational and adolescent-focused programming for youth in detention. Volunteers must pass a criminal background check and attend an initial volunteer orientation. For more information, please call 206-477-9910.

Join the Youth Chaplaincy Coalition

- The Youth Chaplaincy Coalition is a non-King County affiliated group of like-minded individuals and churches who seek to provide services in a faith-based context to youth in detention. The group also trains youth advocates to be chaplains, mentors, and counselors for youth who need re-entry help once they’ve left detention. To find out more, check out their website and Facebook page, or contact Rev. Terri Stewart directly at ycc-chaplain@thechurchcouncil.org or 425-531-1756.

Become a Big Brother or Big Sister

- Big Brothers Big Sisters of Puget Sound provides children facing adversity with strong, professionally supported one-to-one relationships. They are always looking for adults eager to positively impact a child and improve their community at the same time. Big Brothers in are especially in high demand. By spending a few hours a month bonding with a child, “Bigs” dramatically increase the chances that their “Littles” will achieve higher aspirations, avoidance of risky behaviors and obtain educational success. Want to learn more about becoming a Big Brother or Big Sister? Please email StartSomething@bbbsps.org or call BBBS at 877.700.BIGS.

Become a 4C Coalition Mentor

- The 4C Coalition is a collaborative effort to increase the number of African-American mentors dedicated to mentoring the disproportionate number of African-Americans and other youth of color involved in King County’s juvenile justice system. The 4C Coalition is dedicated to uplifting at-risk youth and ensuring that they graduate from high school and avoid gangs, violence, addictions and incarceration. To find out more about donating or mentoring for the coalition, visit their website.

Become a Dependency CASA

- A Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) is a trained volunteer who represents the best interests of children as they are taken through the legal process. These trained volunteers investigate the case and inform the court, help identify resources to address a child’s special needs and recommend temporary and permanent plans for the child. The Dependency CASA Program serves children up to 11 years old who have allegedly been abused and/or neglected. The process focuses on the best interests of the child. The court will try to reunite a family if conditions at home improve sufficiently.

Become a Foster Parent

- Many — if not most — of the youth involved in the juvenile justice system on any given day have experienced a period of inconsistent housing and care-giving. State social workers often struggle to find appropriate homes for foster youth and runaways to stay at because there is a shortage of foster parents available for adolescents. Increasing the number and diversity of foster care placement options can help to identify placements timely and ensure youth have a safe and desirable place to stay. Find out more about becoming a foster parent on the state’s Department of Social and Health Services website.

Calendar

Check back here for updates on community engagement events coming later this year. Our calendar will also list events led by other local governments, partnerships, non-profits and community organizations.

King County is now in the process of creating partnerships with local school districts, police departments, cities, and non-profits to implement data and community-informed solutions in neighborhoods most affected by racially disproportionate school discipline, arrest rates, court involvement and detention stays. More information about organized discussions and outreach in these communities will be available this fall.